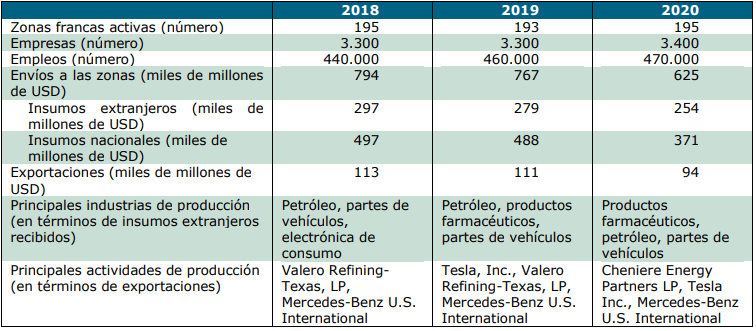

U.S. free trade zones are an important part of the U.S. trade regime, according to information from the World Trade Organization (WTO).

In 2020, these zones received foreign shipments equivalent to 10.6% of U.S. imports and employed 470,000 people (about 3.8% of U.S. manufacturing employment).

FTZs continue to be governed by the Free Zone Act of 1934, as amended, and CBP regulations (19 C.F.R. Part 146).

As of 2020, there were 195 active FTZs, with each U.S. state maintaining at least one; they remain outside U.S. Customs territory for duty and prohibited goods purposes only.

Panorama general de las zonas francas, 2018-2020.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) oversees FTZs through audits and inspections.

Among others, other local, state, or federal regulations regarding environmental, safety, and labor measures are enforced.

Although retail trade activities cannot be carried out in FTZs, almost all other activities such as assembly, cleaning, manufacturing, mixing, blending, processing, repackaging, repair, recovery, storage, testing, and destruction of goods can be carried out.

Generally, FTZs are established by a public authority, such as a port or city, and operate under a grant from the FTZ Council (composed of the Secretaries of Commerce and the Treasury), which regulates all U.S. FTZs.

Free Trade Zones

The manufacture of certain products and product groups and the conduct of certain activities are either prohibited by regulations or are not authorized in practice by the FTZ Board for a variety of reasons.

For example, the production of alcohol, tobacco, firearms, steel, textiles and sugar and the mixing of petroleum products are not permitted.

Some of these restrictions stem from issues related to tax evasion or security, but many reflect trade concerns such as circumvention of quotas or other trade measures, or apply to products that have traditionally been sensitive to imports.

Nevertheless, a wide range of activities, particularly production and distribution, take place in free trade zones.

![]()